By Ben Stahnke

A Political Ecology of Expulsion, Racism, and Violence in the US-Mexico Border Region

A political border is both an idea and a material phenomenon: for those who live in their shadow, this fact can be observed both in the physical barriers—the looming walls, the militarized security, and the razor wire—and in the impact that such an imposing physicality has upon one’s daily life. In Walled States, Waning Sovereignty, political scientist Wendy Brown observed that, “nation-state walling responds in part to psychic fantasies, anxieties, and wishes and does so by generating visual effects and a national imaginary apart from what walls purport to ‘do.’”[1] Fortified political borders—border walls—both shape and respond to not only the material conditions of a nation-state, but to ideological structures as well. In Border People: Life and Society in the U.S.-Mexico Borderlands, border historian Oscar J. Martinez noted that, “borderlands live in a unique human environment shaped by physical distance from central areas and constant exposure to transnational processes.”[2] For the residents of a borderland, the border dominates one’s immediate physical life, as well as the thoughts experienced about such a life; yet the shadow of a border region looms large—over the history as well as the contemporary politics of the region.

In the United States in 2019, the current administration rose to power—in part—on the promise of a large-scale and militarized border wall along the 1,954 miles of the nation’s southern border; a wall designed to stem the northward flow of migration; a wall to separate the have-nots from the haves. The right-wing president Trump ham-handedly exclaimed that, “[t]his barrier is absolutely critical to border security. It’s also what our professionals at the border want and need. This is just common sense.”[3] But, to a critical eye, the so-called common sense of politicking is never quite what it appears to be at face value. The common sense of rightism is, in this case, a xenophobia made manifest in a policy strategy. It is a response to a rapidly changing world—both climatologically and geopolitically. And it is, as Ian Angus noted in Facing the Anthropocene, “a call for the use of armed force against starving people.”[4]

In Planning Across Borders in a Climate of Change, Michael Neuman noted that, "borders are always dynamic, ever shifting. Borders are human constructs enshrined in laws, treaties, regulations, strategies, policies, plans, and so on. We draft them, modify them and erase them at our will. We create, and recreate them, and cannot escape them.”[5] Yet, borders are not simply political in nature; they are economic as well. And these political economic phenomena have a history which is important. Under capitalism, borders are uniquely capitalistic; their logistical and material functions directed not only by security and military interests, but by banking, trade, and distribution interests as well. The 2011 publication of the World Bank, Border Management Modernization, defined a border as:

"...the limit of two countries’ sovereignties—or the limit beyond which the sovereignty of one no longer applies. The border, if on land, separates two countries. Crossing the border means that persons, and goods must comply with the laws of the exit country and—if immediately contiguous—the entry country. [...] Borders are not holistic. Different processes can take place at different places. For example, a truck’s driver may be cleared by immigration at the border, but the goods transported in the truck may be cleared at an inland location. Borders then essentially become institution-based and are no longer geographic."[6]

As intricate complexes of geographical, institutional, and administrational factors, borders are thus managed, maintained, and reformed by a host of political and economic forces. However, as the sociologist Timothy Dunn observed in The Militarization of the U.S.—Mexico Border, “Such issues are too important to be left to the discretion of bureaucratic and policy-making elites, or to be defined by jingoistic demagogues, who scapegoat vulnerable groups.”[7] Under capitalism, and along the southern United States border in particular, the erection of fortifications along the border delineation are entirely swayed by such jingoistic demagoguery.

As the World Bank’s Border Management Modernization argued, “inefficient border management deters foreign investment and creates opportunities for administrative corruption.”[8] Under capitalism, and under the aegis of jingoistic, racist, and conservative policies following the spirit of a new global Manifest Destiny, an inefficiently-managed border equates to a loss of potential profit: an unthinkable evil where capitalism’s logic of profit über alles prevails. And as Tim Marshall observed in The Age of Walls, “[w]alls tell us much about international politics, but the anxieties they represent transcend the nation-state boundaries on which they sit [...] President Trump’s proposed wall along the US-Mexico border is intended to stem the flow of migrants from the south, but it also taps into a wider fear many of its supporters feel about changing demographies.”[9] The land currently identified as the Mexico-United States border has seen, over time, its share of shifting demographies. The national anxieties and fears which presently add the requisite degree of legitimation to the Mexico-United States border wall are, in truth, the fears of a white settler—a stranger upon a land to which he does not belong.

PRE-CONQUEST

The present-day Mexico-United States borderland was not always defined by the administrational and jurisdictional limits of the Mexican and American nation-states. In truth, the region has been well-populated since at least the onset of the Younger Dryas and the Last Glacial Period—and human habitation has been suggested in the southern region of North America for at least 18,500 years. The historian Paul Ganster noted that the region itself, “has a human history stretching back approximately twelve thousand years. The Americas in 1492 are estimated to have had a population of 60 million; 21 million, or 35 percent, of this total are thought to have lived in Mexico.”[10] The imposition of the present day border region of Mexico and the United States fractured—both geographically and socially—a landscape and peoples for whom no such fracture previously existed. Despite the mythos, colonization did not—in almost every instance—occur in wild, unsettled lands, but in lands abundant with inhabitants. The very essence of colonialism is at once bound up in a logic of displacement, genocide, and denial.

In Border Visions: Mexican cultures of the Southwest United States, anthropologist Carlos Vélez-Ibáñez noted that it was “highly likely that major parts of Northern Greater Southwest were well populated at the time of Spanish expansion in the sixteenth century,”[11] with the inhabitants of the region occupying socially and economically complex “permanent villages and urbanized towns with platform mounds, ball courts, irrigation systems, altars, and earth pyramids.”[12] Vélez-Ibáñez went on to note that, “at the time of [Spanish] conquest, the region was not an empty physical space bereft of human populations but an area with more than likely a lively interactive system of ‘chiefdom’-like centers or rancherías, each with its own cazadores (hunters), material inventions, and exchange systems.”[13] The majority of the pre-conquest inhabitants of the region were, according to Paul Ganster:

"what early Spanish explorers termed ranchería people, those who lived in small hamlets with populations only a few hundred each. Such settlements, often scattered over large surrounding territories, relied on wild foods as much as on planted crops. Where favorable agricultural conditions permitted, larger villages and more densely settled subregions existed. [...] Along the Rio Grande an estimated forty thousand people, practicing intensive agriculture, lived in highly organized villages."[14]

The notion that European colonization and settlement occurred in a depopulated wilderness is, as mentioned, naught but a myth of settlement—an ahistorical tool of legitimation for the children of settlers. In the much-lauded Changes in the Land, historian William Cronon observed that, “It is tempting to believe that when Europeans arrived in the New World they confronted Virgin Land, the Forest Primeval, a wilderness which had existed for eons uninfluenced by human hands. Nothing could be further from the truth.”[15]

The story of the pre-conquest border region is, as is the story of all of the Americas, one of violent displacement, of harsh and rapid resource extraction, and of pillage. In Open Veins of Latin America: Five Centuries of the Pillage of a Continent, Eduardo Galeano lamented that:

"Latin America is the region of open veins. Everything, from the discovery until our times, has always been transmuted into European—or later United States—capital, and as such has accumulated in distant centers of power. Everything: the soil, its fruits and its mineral-rich depths, the people and their capacity to work and to consume, natural resources and human resources. Production methods and class structure have been successively determined from outside for each area by meshing it into the universal gearbox of capitalism."[16]

The indigenous peoples of the Mexico-United States border region lived, and still live—along the border region’s western half—in the warmth and the aridity of the High Sonoran Region; an area characterized by:

"...high aridity and high temperatures. Typically, about half of the eastern part of the region’s precipitation falls in the summer months, associated with the North American monsoon, while the majority of annual precipitation in the Californias falls between November and March. The region is subject to both significant inter-annual and multi-decadal variability in precipitation. This variability, associated with ENSO, has driven droughts and foods and challenged hydrological planning in the region."[17]

The area itself is also mountainous—“criss-crossed by a maze of inhospitable ranges that divide the area into isolated subregions.”[18] Further, according to the Commission for Environmental Cooperation (CEC), and by way of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Ecological Restoration in the U.S.-Mexico Border Region report, the present day border region is itself home to no fewer than seven unique ecosystems: the Californian Coastal Sage, Chaparral, and Oak Woodlands, the Sonoran Desert, the Madrean Archipelago, the Chihuahuan Desert, the Edwards Plateau, the Southern Texas Plains, and the Western Gulf Coastal Plain.[19]

While the Mexico-U.S. border region now is a “place where two historical-cultural tectonic plates are grinding against each other,”[20] it is a region whose delineations and delimitations have only been imposed recently: a “result of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848, [which] has never changed location except for the modifications introduced by the Gadsden Purchase of 1853 and one small sliver of land called ‘El Chamizal’ just north of the Rio Grande in El Paso that was set aside in 1963.”[21] Prior, however, to the American and Mexican treaties, and prior to the delimitation of the present-day border region, the area was home not only to indigenous peoples, but also to Spanish colonial aspirations.

CONQUEST

Beginning with the 1492 journey of Christopher Columbus—a man who, on that very same 1492 journey, observed that, “[o]ne who has gold does as he wills in the world, and it even sends souls to Paradise”[22]; an insightful comment on the journey’s primary motivations—the resultant Spanish conquest of the Americas over the next several centuries was no less than a systematic genocide.[23] The indigenous peoples of the Americas suffered greatly under Spanish colonialism, and “[i]n little more than a century,” the economist and historian Michel Beaud observed, “the Indian population was reduced by 90 percent in Mexico (where the population fell from 25 million to 1.5 million), and by 95 percent in Peru. Las Casas estimated that between 1495 and 1503 more than 3 million people disappeared from the islands of the New World. They were slain in wars, sent to Castile as slaves, or consumed in the mines and other labors.”[24] The Council of Castile, “resolved to take possession of a land whose inhabitants were unable to defend themselves,”[25] and the wealth of the Spanish nobility increased exponentially—the cost being—both simply and brutally—genocide, slavery, and the rapacious extraction of resources. At its heart, the Spanish colonial impetus was one dominated by themes of greed, oppression, theft, murder, personal ennoblement, and of continued, relentless conquest. Virtually every colonial effort from the era seems to be dominated by these themes. Paul Ganster noted that:

"In the five decades after Columbus, the Spanish made a series of expeditions: Juan Ponce de Leon’s 1513 expedition to Florida; Alonso Alvarez de Pineda’s 1519 voyage around the Gulf of Mexico; Estevao de Gomes’s 1524-1525 recorrido (trip) up the northeastern seaboard; Pedro de Quejo’s 1525 voyage from Espanola to Delaware; Hernando de Soto’s 1539-1543 visit to what is today Florida and the Atlantic Southeast; and Joao Ridrigues Cabrilho’s 1542-1543 expedition along the California coast."[26]

The Spanish colonial expeditions had as their goal the procurement of wealth for the Spanish crown, as well as the securement of lands in the New World under Spanish sovereignty. “The production of sugarcane for rum, molasses, and sugar, the trade in black slaves, and the extraction of precious metals established considerable sources of wealth for Spain throughout the sixteenth century.”[27] For the Spanish, this growing wealth—following on the heels of the dominance of a growing territory—only fed the desire for more wealth; and where the “wealth of the kingdom depended upon the wealth of the merchants and manufacturers,”[28] there followed the insatiable growth of the Spanish conquest in and among the Americas.

Spanish conquest secured, for the monarchs of Castile, a vast majority of the land in the Americas, and, at its height, governance was divided amongst several viceroyalties—the Viceroyalty of New Spain, the Viceroyalty of Peru, the Viceroyalty of New Granada, and the Viceroyalty of Rio de la Plata. The viceroyalties, with their capitals centered in such present day metropoles as Mexico City, Lima, Bogotá, and Buenos Aires, were subject to the dictates and whims of the monarchs of Castile, where:

"...king[s] possessed not only the sovereign right but the property rights; he was the absolute proprietor, the sole political head of his American dominions. Every privilege and position, economic political, or religious came from him. It was on this basis that the conquest, occupation, and government of the [Spanish] New World was achieved."[29]

In the era of European empire, nascent capitalism, and the carving up of the world by the dominant European powers—expressions of both rapaciousness and technological might—monarchical whims became increasingly protectionist. “As other European powers became interested in the [present-day border] region and Spain’s interest in protecting its empire grew, the Far North was increasingly the focus of attempts to impede intrusions. Defense against the spreading influence of the French, English, and Russians became one of the main foundations of settlement.”[30]

THE MOVE NORTHWARDS: CHRISTIANITY AND THE GUN

Where late Spanish feudalism was still heavily dominated by the sphere of influence of the Catholic Church—a vestige of the ancient Roman imperialism, enamored with imperialism’s political logics of expansion and accumulation—there both went, hand-in-hand, upon the American landscape in the form of the northward settlements. Where the Spanish conquest of the Americas was concerned, both military and church acted in strategic coordination to secure lands and resources for the Crown. On this, Paul Ganster observed that, “[i]n order to pacify and populate the area at minimal cost, the Crown came to rely on two institutions with funds and personnel of their own: the military and the religious orders. This approach gave rise to the classic duo of European settlement in the North: the presidio and the mission.” Here, the unification of Christianity and the gun, of religious and militaristic dominance, emblematized the dialectic of late feudal political dominance—and it grew steadily northward upon the arid landscapes of what would later become the southern United States.

Over time, many of the early presidios— walled, defensible towns peopled by soldiers, officers and their families—grew to become permanent towns, and gradually, “warfare against raiding natives gave way to campaigns by new settlers and the government to distribute food and supplies to indigenous populations.”[31] Similarly, and alongside the presidios, the missions grew northward—the slow, insidious creep of European settlement seeped into abutting indigenous communities—and within a hundred years of Spanish conquest, “a string of missions stitched from east to west, cross the frontier and up the Pacific coast from Sinaloa to California.”[32] Alongside the presidios, the missions were also “expected to help pacify and incorporate Native Americans; they reduced into settled units the diverse and complex populations, particularly those who were semisedentary or nomadic.”[33] Thus both soldier and priest worked to settle the northern Spanish frontier in ways which were violent, politically recuperative, and emblematic of late-feudal/early-capitalist European colonization the world over.

However, soldier and priest alone did not colonize and subjugate the American frontera. Another, arguably stronger force followed in their shadow: the civilian settler. During the colonial period of 1492-1832, an estimated 2 million Spanish citizens flocked to the Americas to both colonize and settle the land. “Closely behind the Jesuits,” historian Samuel Truett observed, “came Spanish miners, merchants and ranchers. [...] Yet there was more to these migrations than the lure of profit, for Crown officials expected miners, merchants, and ranchers to defend as well as transform space. To hold the borders of the body politic, whether against Indians or other empires, colonists also went north as civilian warriors, with gun in hand.”[34] Civilian settlers—greater in number than the soldier of the presidio or the padre of the mission—came at first from Spain, and then Mexico City. But gradually, however, “immigrants were drawn from adjacent provinces. Sinaloa supply colonists for Sonora and Baja California, and these in turn supplied settlers for Alta California.”[35] As Paul Ganster noted, two distinct characteristics made these new Spanish frontier populations unique: racial diversity and the growing prevalence of wage labor.

"The inhabitants were of varied and mixed ethnicities, including Native Americans from all over the North and from central Mexico, as well as African Americans. Frontier society was also characterized by the prevalence of wage labor, which spread from the mines and urban settlements to agricultural areas, as a result of the high return on investment in the region, the need for skilled labor, and the location of the mining towns in areas of sparse indigenous population."[36]

By the mid-1700s, however, Spain’s northward expansion of the church and the gun, of presidio and mission, and of capitalist wage labor and colonial settlement began to wane. “Practical frontiers had to be drawn, and the imperial emphasis shifted from northward expansion to defend and consolidation.”[37] The unification of humans and nature, and the transformation of native American nature into something resembling European manorial economy was, in part, the mission of the mission; where, for the Jesuits, “the incorporation of humans and nature were part of the same equation. To attract converts and build mission economy, they sought to transform Sonora into a world of pastures and fields.”[38] Such efforts, however, were not only stymied by native populations unaccustomed to such an economy, but by nature itself. “Often,” noted Truett, “natural disorder followed in the wake of social disorder.”[39] Social, political, and environmental pressures all lent themselves to the halting of Spain’s northward movement, and, with the onset of the nineteenth century, an increasing friction between the New Spain and the Old, and the Napoleonic invasion of the Iberian peninsula, New Spain soon declared its independence from the Old.

AMERICAN IMPERIALISM AND MANIFEST DESTINY

Mexican independence from Spain, and the slow emergence of the present day Mexico-United Stated border delimitation, did not occur all at once; but through an overdetermination of historical, political, and economic factors. The geographer Joseph Nevins noted that:

"The origins of the U.S.-Mexico boundary are to be found in the imperial competition between Spain, France, and England for ‘possessions’ in North America. The Treaty of Paris of 1783, which marked the end of the American war for independence, resulted in the United States inheriting the boundaries established by its English colonial overseer. [...] The Treaty of Paris thus resulted in a situation where the United States shared its southern and western boundaries with Spain."[40]

New Spain qua the newly-independent nation of Mexico similarly found its borders shifting in the tumult of the nineteenth century. Independence brought with it a removal of the sovereignty of the Spanish Crown, but also a new type of vassalage to France, for whom it became, essentially a client state.[41] The eyes of the United States soon turned to Sonora, and “[b]y the time Americans began to dream of Sonora, Sonora was a dream that had traveled across national borders, halfway around the world, and back again.”[42] Capitalist interest in the rich Sonoran region—inextricably entangled with Europe’s settler colonial interests in the New World—continued unabated, and shifting borders, losses of heretofore sovereign interests, and a geography in flux all presented themselves as ripe fruits for the capitalist interest. Historian Samuel Truett observed that the German geographer Alexander von Humboldt’s Political Essay on the Kingdom of New Spain, for example, “was translated into English in 1811 with the goal of luring European capital to Mexican mines. And the idea of unfinished conquests appealed to a British capitalist class that was beginning to invest energetically at home and abroad.”[43] Equally true of both the nineteenth century and the present day, nothing quite draws capitalist interest like political instability, exploitable economies, and the dream of so-called “opportunity” in the service of personal profit.

The 1821 independence of Mexico from Spain brought with it many new instabilities. Historian Rachel St. John noted that, “[t]erritorial competition defined North America in the early nineteenth century. At the beginning of the century, the continent was still very much up for grabs.”[44] And Samuel Truett noted that, “[w]ith independence in 1821, [Spanish] trade barriers were dissolved, to the great relief of entrepreneurs.”[45] For both the new nation of Mexico and the increasingly imperialistic United States, political upheavals, economies-in-waiting, and geographical instabilities became the driving themes of the nineteenth century in North America—particularly where the future Mexico-U.S. border region was concerned. Paul Ganster noted that, “During the relatively brief span from Mexican independence in 1821 to the end of the between the United States and Mexico in 1848, Spain’s far-northern frontier territories became borderlands—the relatively unrefined and frequently contested terrains between Mexico and the United States.”[46] Mexico’s recent independence, the machinations of empire, and the increasingly contested borderlands entailed by the Louisiana Purchase and Texas soon drove the United States and Mexico to war. On the Louisiana Purchase, Joseph Nevins noted that:

"Napoleon compelled Charles IV of Spain to cede an enormous territory west of the Mississippi River to France in 1800 in return for lands in Italy. [...] Three years later, however, Napoleon sold the vast territory to the United States for $15 million—an exchange known as the Louisiana Purchase—without taking Spanish opinion into consideration. [...] Almost immediately after the signing of the treaty, however, U.S. President Thomas Jefferson foreshadowed U.S. expansionist designs on Mexico, expressing the view that Louisiana included all lands north and east of the Rio Grande, thus laying claim to Spanish settlements such as San Antonio and Santa Fe."[47]

With the Louisiana Purchase nearly doubling the size of the young and land-hungry United States, questions and conflict of delimitation and boundary soon arose with the newly-independent Mexico. Historian Oscar Martínez noted that:

"With independence achieved in 1821, Mexico inherited from Spain the challenge of safe-guarding the vast northern frontier. More population was needed to strengthen the defenses of California and Texas particularly. Following policies begun by Spain, Mexico in the 1820s allowed entry into Texas of large numbers of immigrants from the United States in order to further populate that sparsely settled province. [...] Within a short time Mexico would realize what a volatile situation it had unwittingly created within its own borders."[48]

With eastern and western Florida having already been acquired from Spain between 1795 and 1819, the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, and the cession of northern lands in Minnesota by Britain in 1818, the eyes of the United States gazed hungrily at the lands north of present-day Mexico in Texas, the now-southwestern states of Arizona, New Mexico, and California. These U.S. imperialist-expansionist efforts—efforts which emerged, ideologically, as the concept of Manifest Destiny—quickly brought the United States and Mexico to war. “Once the philosophy of Manifest Destiny took firm hold in the European American mind the outcome seemed clear: sooner or later the United States would detach and annex Mexico’s northern territories.”[49] In a now well-known strategy of American imperial-economic interventionism, the United States acted quickly to foment dissent in the northern Mexican territory; foreshadowing war and military annexation. Joseph Nevins observed that:

"In the aftermath of Mexican independence in 1821, U.S. economic actors exploited political instability in what today is the Southwest. Through their long-distance trade routes, the associated socio-cultural ties they engendered, and sponsorship of raids by Native groups against Mexican communities and Mexico’s emerging state apparatus, they helped to undermine those communities and the state."[50]

After the 1836 Texas declaration of independence from Mexico—an independence fed, largely, by American settlement in the region—and the eventual 1845 annexation of Texas by the United States, an annexation that faced popular approval by Texan “pro-slavery southerners,”[51] the doctrine of Manifest Destiny—the idea that “it would be beneficial to both countries to absorb Mexico into the United States”[52]—diplomatic relations between the United States and Mexico rapidly deteriorated and war loomed on the horizon. In the early part of 1846, U.S. President James Polk sent troops to the Rio Grande, hoping to provoke Mexico into war, and “to make Mexico recognize the Rio Grande as Texas’ southern boundary, and (perhaps most importantly) to face Mexico to cede California and New Mexico to the United States.”[53] War, by way of American provocation, of course did erupt, and the Mexican-American War—over a span of two years—claimed the lives of over 25,000 Mexicans and 13,500 Americans.

The war ended on February 2, 1848 with the signing of the treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo—officially entitled the “Treaty of Peace, Friendship, Limits and Settlement between the United States of America and the Mexican Republic”—and the new southern border of the United States was set at the Rio Grande, with the additional land concession of the Gadsden Purchase in 1853 solidifying the current southern border of the United States. Historian Rachel St. John recorded that:

"With U.S. soldiers [in 1848] occupying the Mexican capital, a group of Mexican and American diplomats redrew the map of North America. In the east they chose a well-known geographic feature, the Rio Grande, settling a decade-old debate about Texas’s southern border and dividing the communities that had long lived along the river. In the west, they did something different; they drew a line across a map and conjured up an entirely new space where there had not been one before."[54]

The newly designated southern delimitation of the United States was, as all borders tend to be, an imaginary line with very real material consequences. The United States border severed communities and families from each other, arbitrarily divided homogenous ecosystems and species, and drew, essentially, a series of straight lines in the sand from El Paso and Ciudad Juárez to the Pacific Ocean. The historian Thomas Martin observed that:

"The United States pioneered the idea of the straight-line geometric border, based on surveying techniques that (bizarrely, if you think about it) use magnetism and the position of stars rather than the actual lay of the land or ethnic considerations. The habit was formed even before the Revolution, when the proprietors of Maryland and Pennsylvania hired the astronomers Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon to discover the exact boundary between their colonies."[55]

The straight-line approach to border delimitation occurred, in 1848, by “U.S. and Mexican officials [...] simply drawing straight lines between a few geographically important points on a map—El Paso, the Gila River, the junction of the Colorado and Gila rivers, and San Diego Bay.”[56] Importantly, the only “natural” boundary delimitation along the southern border of 1848the Gila River, was made obsolete and irrelevant by the 1853 Gadsden Treaty. The unique straight-line peculiarity of the western portion of the United States southern border would soon prove to provide numerable economic, political, and security consideration for the United States—considerations which still occur to this day.

THE BORDER SINCE 1848

Since 1848, the border management trend for the southern delimitation of the United States has taken on an increasingly violent character. Further, the primary subthemes of this violence have been racism, economism, protectionism, and militarism. As Joseph Nevins observed, “[i]t took many decades for the United States to pacify the area along its southern boundary, as part of a process of bringing ‘order’ and ‘civilization’ to a region perceived as one of lawlessness and chaos.”[57] For capitalism, order and civilization equate to the often violent and repressive impositions of federal authority. Rachel St. John noted that, “In the years following the boundary line’s creation, government agents would mark the desert border with monuments, cleared strips, and, eventually, fences to make it a more visible and controllable dividing line,”[58] a dividing line which “allowed the easy passage of some people, animals, and goods, while restricting the movement of others.”[59]

The Mexico-U.S. border in the second half of the nineteenth century was never quite a settled matter. The legal agreements between the governments of the United States and Mexico stood, yet many expansionist-minded Americans—the so-called filibusters—saw fit to make incursions into Mexican territory in an effort to establish new southern slave states for the United States—actions to which the United States often turned a blind eye. The filibustering incursions both preceded and followed the Mexican-American War, but, as Oscar Martínez observed:

"The years following the U.S.-Mexico War have been called the golden age of filibustering. Men seeking fortune or power cast their eyes on the resource-rich and thinly populated northern tier of Mexican states. War veterans, forty-niners, and miscellaneous travelers during the late 1840s and early 1850s had portrayed the region in colorful, exotic, and economically attractive terms."[60]

Martínez went on to observe that the early filibustering efforts—efforts and excursions which lasted well into the early part of the 1900s—constituted “a central part of U.S. expansionist aggression directed at Mexico. The periods of the greatest unlawful invasions organized in the United States coincide with weakness and instability in Mexico.”[61] The filibustering and pseudo-filibustering excursions added heavily to the distrust between Mexicans and European Americans, and it was not until the 1930s and 1940s that “fear [began] to dissipate south of the border”[62] of future filibuster incursions.

As a largely un-policed, heavily-contested, and volatile region for the bulk of the nineteenth century, the onset of the twentieth century saw an increasing trajectory of control along the United States’ southern border. In July 1882, the United States and Mexico formed “a new International Boundary Commission and charged it with resurveying and reaping the border, replacing monuments that had been displaced or destroyed, and adding monuments so that they would be no more than 8,000 meters apart in even the most isolated stretches of the border and closer in areas ‘inhabited or capable of habitation.’”[63]

The Mexican Revolution of 1910, violence, diplomatic disputes, and an economic instability which had disrupted the transborder economy, all led towards an increasing militarization of the Mexico-U.S. border in the early 1900s. Rachel St. John noted that the persistent smuggling of cattle, narcotics, and immigrants—all fallouts from the Mexican Revolution—led to the United States government’s (now-persistent) decision to dispatch troops to its southern boundary to “insure that revolutionaries did not access American arms or launch invasions from U.S. soil.”[64] The increasing militarization of the southern border was also, as noted by sociologist Timothy Dunn, “defined by efforts to maintain control over the flow of Mexican immigrant workers into the United States, typically in ways that also significantly affected Mexican Americans.”[65] Increasing control of the cross-border flow of migrants and goods—the “revolving door” immigration policy—led to the establishment in 1924 of the U.S. Border Patrol—by way of the Immigration Act legislation—as “the chief guardian of the ‘revolving door’ and the main agent of the comparatively less severe forms of border militarization carried out during ensuing decades.”[66] Historian Kelly Hernández observed that the newly-designated “Border Patrol officers—often landless, working-class white men—gained unique entry into the region’s principle system of social and economic relations by directing the violence of immigration law enforcement against the region’s primary labor force, Mexican migrant laborers.”[67]

Since 1924, the U.S. Border Patrol—now a component of the United States Department of Homeland Security—has grown to become a law enforcement agency with almost 20,000 agents and officers and an almost 4 billion dollar yearly budget.[68] Expanded arrest authority,[69] an expansion of legal jurisdiction, and an increase in the paramilitary character of the agency[70] have all occurred in the twentieth century, and as the twenty-first century is now underway, the trajectory of this increasing militarization appears to move forward unabated. The Secure Fence Act of 2006 provided for the construction of around 700 miles of fortified fencing, and Trump’s 2017 Executive Order 13767—“Border Security and Immigration Enforcement Improvements”—all represent the increasing militarization of the southern border; a militarization which is at once troublesome and not-unexpected. Instability, immigration, cross-border illegal (and legal) trade, and the necessity for the United States to not only secure its southern border from illicit economies—for the United States must have total economic control—but to flex its imperial might, have all been factors in the increasing militarization of the southern border. The escalation of the so-called “War on Drugs,” and an increase in migrant populations from Mexico, Central, and South America due to political and climatological instabilities have all lent themselves to an increase in the militaristic fortification along the southern border—yet the story is far from over.

THE BORDER AND THE WALL

In a January 2018 tweet, the white nationalist Donald Trump exclaimed that, “[t]he Wall is the Wall, it has never changed or evolved from the first day I conceived of it”[71]; but the truth of the matter is that “The Wall” itself has long been in the works—the logical outgrowth of a lengthy history of colonization, settlement, and a protectionist, hegemonic political strategy in the face of rising resource in- equalities and modern-day global instabilities. What began as a disputed boundary zone—a relic of the European imperial struggles of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries—and once “the site of considerable, wide-ranging military and security measures”,[72] has not, on a fundamental level, changed. The land is still mountainous and arid, indigenous populations still inhabit the area, yet something fundamental has changed about the border region. The increase in militarization, the growing spans of the border wall, the surveillance, the security, and the police presence; all of these have progressed as the United States has worked to fortify itself from Mexico and the southern Americas, to stem the flow of immigration from an increasingly unstable and climatologically-shifting south. The border region is, on one level, naught but a line in the sand; a forced agreement between the United States and Mexico propped up by a lengthy and violent history of imperialism, capitalism, and European colonization in the Americas. Yet, for those who live with and around the border, it is a material reality—and a harsh one at that.

Wendy Brown wrote that:

"Ancient temples housed gods within an unhorizoned and overwhelming landscape. Nation-state walls are modern-day temples housing the ghost of political sovereignty. They organize deflection from crises of national cultural identity, from colonial domination in a postcolonial age, and from the discomfort of privilege obtained through superexploitation in an increasingly interconnected and interdependent global political economy. They confer magical protection against powers incomprehensibly large, corrosive, and humanly uncontrolled, against reckoning with the effects of a nation’s own exploits and aggressions, and against dilution of the nation by globalization."[73]

The US-Mexico border wall is an effort to shore up the vestiges and appearances of imperial might; it is a permanent problematization and the material admission of an unwinnable frontier. The waning imperial sovereignty implied by the US-Mexico border wall is made manifest in the materiality of its vastness and scale.

For the structural Marxist dimensions of border studies and political ecology, the increasing militarization of the U.S.-Mexico border presents a unique opportunity for both critical analysis and the application of the dialectical materialist lens. On the one hand, the militarization, fortification, and planned walling of the United States’ southern border is a material response to movement: to migration and to economic flow. Yet, on the other hand, the construction of a continuous border wall along the Mexican boundary line means something in regard to the state of the union itself: it emerges conspicuously at a time of great upheaval—an intersectional overdetermination of political, social, economic, and ecological tumult.

In a December 2018 article entitled “Walls Work,” the US Department of Homeland Security (DHS) wrote that they were, “committed to building a wall at our southern border and building a wall quickly. Under this President, we are building a new wall for the first time in a decade that is 30-feet high to prevent illegal entry and drug smuggling.”[74] Federal funding toward wall construction has increased steadily since 2017. In fiscal year (FY) 2017, for example, United States Congress provided the DHS with 292 million dollars, while in FY2018 that number jumped to 1.4 billion in funding for border wall section-constructions. The DHS, through their own admission, seek to “strengthen security and resilience while also promoting our Nation’s economic prosperity.”[75] According to the DHS 2019 budget, FY2019 saw an allocation of “$1.6 billion for 65 miles of new border wall construction in the Rio Grande Valley Sector to deny access to drug trafficking organizations and illegal migration flows in high traffic zones where apprehensions are the highest along the Southwest Border.”[76] And, reflecting the Pax Romana/barbaricum rhetoric of Imperial Rome, the DHS stated that:

"Securing our Nation’s land borders is necessary to stem the tide of illicit goods, terrorists and unwanted criminals across the sovereign physical border of the Nation. To stop criminals and terrorists from threatening our homeland, we must invest in our people, infrastructure, and technology."[77]

Echoing Michael Neuman’s assertion that, “[b]orders are always dynamic, ever shifting,”[78] the political philosopher Thomas Nail observed that, “The US-Mexico border is in constant motion. The border does not stop motion, nor is it simply an act of political theater that merely functions symbolically to give the appearance of stopping movement. The border is both in motion and directs motion.”[79] The United States is an empire in the truest sense of the word; and, further, it is the empire of the modern era. Thus, by extension, its borders are imperial borders. To better understand not only the ways in which the US deals with its border regions, but also why it is driven to militarize and fortify them, and what the future may hold for the US borderlands, a historical lens is thus of great benefit.

The word “border” itself derives from the Proto Indo-European (PIE) root word *bherdh- ; a term which means to “cut, split, or divide.” The word itself, in the modern usage of the term, has been inherited from Middle English bordure, from the Old French bordeure, and the Middle High German borte. While, initially, the European usage of the word held heraldic connotations—as in the trim or border-trim which enclosed heraldic devices such as shields and flags—the term, in the late fourteenth century, came to replace the older term march. March, a now obsolete term for the border—which comes to us from the PIE term *marko—was understood as both “borderland” and “frontier.” The US-Mexico border is, ultimately, all of these things—it is a frontier, a march, and a border; and it is also much more.

As not only a distinct historical borderscape, but a region which represents imperial machinations in the twenty-first centu- ry, the U.S-Mexico border region is one which has much to offer radical political ecology in the way of critical analysis. For example, when we examine historical border regions, such as the Roman frontiers in northern Britain, we are able to derive our ideas from a timeline that has a beginning, an end, and an after. We are able to tell the story of the initial Roman invasion, the period of Roman conquest, Roman consolidation, and, finally, the Roman withdrawal. Thus we are able to view, in toto and from an historical lens, the Roman border regions from their birth until their death. Yet with the southern border region of the United States, we are only able to view a small subsection of this story; we have only a beginning and a middle—and we live during the time of its becoming. While we might be tempted to project our ideas and our abstractions upon the future of this border region, the future, as always, is unwritten. Thus we find ourselves at once limited and quite fortunate. We are limited in the sense that we are only able to tell a part of the story, yet we are incredibly fortunate to have, as an object of critical analysis, a border-in-motion—one upon which a border wall is presently being constructed, and one which, for our purposes, signifies the imperial border-in-motion; a fortified border of capital able to offer us some insights into the protective, racist nationalism of capitalism itself.

As a geographical zone of inquiry, laden with theoretical implications, “the US/Mexico Border is a region unto itself, one that supersedes the more abstract state boundaries on either side and which is considered by the powers that be—whether in Washington, DC; México, D.F.; Austin, TX; or Sacramento, CA—as irrelevant except as a place of passage for goods and people.”[80] The region is both a material-geographical zone and an abstracted set of ideas transposed upon a landscape—it cannot be reduced to either one or the other. Following this, the border can be viewed not simply as a site of motion, but as a layered, nuanced region—overdetermined in its meaning by cultural, political, economic, and ideological currents.

The border is both in motion and controls motion; yet a lens of motion alone is not quite sufficient where critical border analyses are concerned. As the geographer Lawrence Herzog observed, “Boundary zones derive their meaning from a role determined by the workings of the world economy.”[81] Yet, similarly, a lens of economy alone is not enough when it comes to border critique and the articulation of a theory which contains the ability to hold the multivariate factors which, in actu, create the borderscape. In short, to most correctly understand the imperial border, our understanding, and our scope, must of course be dialectical.

The southern United States border is a region in the midst of a great and progressive militarization; a region which increasingly sees the construction of surveillance apparatuses, fence fortifications, detention centers, and border police garrisons. As a region not confined to the material-geographical border-line itself, the border regime of the United States in relationship to its southern border is one which is fed by a large sociopolitical infrastructure of militarized police along and a complicit public —police whose jurisdiction extends far beyond the border-line itself and who target, disproportionately, working people of color; and a public which, by and large, either support the nationalist rhetoric of expulsion, or who are largely unaware of the incredibly vast infrastructure along the border and thus implicitly support its expansion.

During the fiscal year 2019, 2.8 billion US dollars were allocated for the purchase of 52,000 detention beds, while only 511 million dollars were allocated for the transportation infrastructure needed to shuttle those migrants whom the United States has determined illegal out of the nation state’s boundaries.[82] The sociologist Timothy Dunn noted that, “The potentially far reaching implications of the militarization of the U.S.-Mexico border have not been widely considered, as the phenomenon of border militarization has gone largely unrecognized.”[83] The incrementalism of creeping border militarization is one which, as with all incrementalisms, largely goes unnoticed by a distracted and ideologized public.

Violence, and the themes of both expansion and expulsion, define, and have historically defined, the U.S.-Mexico border region; and it is precisely the violent history of the region itself which must define our critical analysis of the region. As the historian Kelly Hernández observed, “the racial violence of immigration law enforcement stemmed from the history of conquest in the U.S.-Mexico border lands.”[84] As an imperial border—fed by the violence of the Spanish conquest and the American acquisitions—the U.S.-Mexico border region is a region defined by its past.

Similar to the Roman fracture of Brigantes territory with the construction of Hadrian’s Wall in Roman Britannia, the United States border, and the growing border wall, does much to not only fracture the indigenous peoples of the region, but, in fact, all regional biota. Eliza Barclay and Sarah Frostenson noted that:

"What’s undeniable is that the 654 miles of walls and fences already on the US-Mexico border have made a mess out of the environment there. The existing barrier has cut off, isolated, and reduced populations of some of the rarest and most amazing animals in North America, like the jaguar. They’ve led to the creation of miles of roads through pristine wilderness areas. They’ve even exacerbated flooding, becoming dams when rivers have overflowed."[85]

Rob Jordan, from the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment observed that:

"Physical barriers prevent or discourage animals from accessing food, water, mates and other critical resources by disrupting annual or seasonal migration and dispersal routes. Work on border walls, fences and related infrastructure, such as roads, fragments habitat, erodes soil, changes fire regimes and alters hydrological processes by causing floods, for example."[86]

And, in an article endorsed by more than 2,500 scientist signatories from across the globe, entitled “Nature Divided, Scientists United: US–Mexico Border Wall Threatens Biodiversity and Binational Conservation,” the renowned biologist Paul Ehrlich commented that:

"Fences and walls erected along international boundaries in the name of national security have unintended but significant consequences for biodiversity [...]. In North America, along the 3200-kilometer US–Mexico border, fence and wall construction over the past decade and efforts by the Trump administration to complete a continuous border “wall” threaten some of the continent’s most biologically diverse regions. Already-built sections of the wall are reducing the area, quality, and connectivity of plant and animal habitats and are compromising more than a century of bi-national investment in conservation. Political and media attention, however, often understate or misrepresent the harm done to biodiversity."[87]

Thus, not only does the fortification and the increasing militarization of the U.S.-Mexico border region fragment indigenous groups, control social motion, and regulate cross-border economy and migration; it shatters ecosystems, fragments habitats, decreases biodiversity, and contributes heavily to the deleterious imposition of a global imperial economy which has set itself against the earth as a destructive and cataclysmic force. Border walls—and the U.S.-Mexico border wall specifically—thus contribute to and catalyze global environmental change in ways that are far reaching, damaging, and destructive. However, the ecological argument should be but one aspect of the overall critique.

As an imperial state by design—founded upon an economy of colonial advancement and cataclysmic extraction—the political and economic tendrils of the United States have, in a relatively short time, crept into all spaces of the earth. First a site of resource and slave extraction for the European feudal powers, next a region of conquest and colonization; the military expenditures, and the calculated machinations of imperial control have pushed the United States to the position of prime suzerain—a global superpower amongst superpowers. Yet its position is held upon a lengthy history of violence, racism, genocide, and slavery; upon the backs of an impoverished working poor, an increasingly stratified social hierarchy comprising a minority élite and a proletarian majority, and a long history of warfare, conquest, and subversion. Having grown from a small collection of European colonies along its eastern shore, the west-ward expansion of settlers, commerce, and the military—the church and the gun— have since displaced the at least 12,000 year habitation by indigenous peoples, imperial claims by various other European feudal powers such as the Spanish and the English, and global resistances in the form of Cold War-era oppositional states such as the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc. Unassailed, the United States appears to do what it wishes, with little respect for international heterodoxy, global ecology, and the subaltern populations against whom it sets itself. Following all of this, its border regime could only ever emerge as a logical extension of not only its political and economic history, but the ways in which it organizes and is organized by its social structure and its military doctrine.

Yet the southern US border is one which has two sides. Where an increasingly “hard” border regime ossifies relationships of us/them, civilization/barbarism, and self/other, the Mexican state finds itself in an increasingly precarious position. The historian Oscar Martínez noted that:

"The historical record reveals an evolving border relationship between Mexico and the United States. Turbulence dominated during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, with serious conflict erupting repeatedly over issues such as the delimitation and maintenance of the boundary, filibustering, Indian raids, banditry, revolutionary activities, and ethnic strife."[88]

Martínez went on to note that:

"Mexican border cities will continue to bear the brunt of the criminal activity that is required to sustain the illegal distribution system that services the insatiable U.S. market. It means more frequent shootings, kidnappings, tortures, killings, femicides, massacres, and mass burial graves involving not only traffickers but innocent people as well."[89]

As an increasingly hostile zone of friction, the US-Mexico border region is thus one which, following the trajectory of militarization, will remain as such until it is no longer. In this regard, there are not only ecological, social, political, and economic implications that can be drawn from a critical analysis of the border region; there are legal, ethical, and philosophical implications that present themselves as well.

LA FRONTERA: CONCLUSIONS AND THEORETICAL CONSIDERATIONS

As a living historical artifact, the US-Mexico border region might be seen as a site of conflict between three modes of production: primitive, feudal, and capitalist. In social metabolic terminology, we might note the friction between the extractive, the organic, and the industrial metabolisms during the historical generation of what is today the border region. And, in the language of social kinetics and kinopolitics, drawn from the theoretical work of the leading materialist political philosopher Thomas Nail, the border itself thus becomes a site of overlap for centripetal, centrifugal, tensional, and elastic forces. The border, thus conceived, is not only a site of confluence between these historically-determinate and theoretical notions, but a site of conflict as well.

In the history of the US-Mexico borderlands, we see the dialectic of confluence and conflict not only of metabolisms, modes, and kinetics, but of inter-metabolic friction. The historian Samuel Truett observed that:

"In the borderlands, history moves us beyond such dichotomies, for here market and state operated in tandem for years, tacking back and forth between national and transnational coordinates. Even more important, it reveals the persisting failures of market and state actors, for neither controlled their worlds as expected."[90]

The US-Mexico borderland is a region that is not only defined by conflict and confluence, but delimited by its ecological parameters as well: it is an arid, mountainous, and vast region. And, to-date, the region is unique in that it is “the only place in the world where a highly developed country and a developing nation meet and interact.”[91] The political scientist Kathleen Staudt noted that international “border regions are an odd sort of integral space with characteristics shared by both sides.”[92] In keeping with its overdetermined nature, the U.S.-Mexico borderscape thus requires that our analytical and critical lenses be similarly overdetermined and dialectical in nature; that is, that we must recognize the complex, contradictory, and co-existing factors that go into the creation of the border and that we avoid reducing or polarizing these factors into either positivist or constructivist categories.

As the philosopher Étienne Balibar has warned:

"The idea of a simple definition of what constitutes a border is, by definition, absurd: to mark out a border is precisely, to define a territory, to delimit it, and so to register the identity of that territory, or confer one upon it. Conversely, however, to define or identify in general is nothing other than to trace a border, to assign boundaries or borders (in Greek, horos; in Latin, finis or terminus; in German, Grenze; in French, borne). The theorist who attempts to define what a border is is in danger of going round in circles, as the very representation of the border is the precondition for any definition."[93]

The US-Mexico border region is, as mentioned previously, always-already an overdetermined phenomenon. One factor alone can not tell us all there is to know about the meaning, the import, and the purpose of the border itself; many factors, forces, and movements (over)determine their existence. The border region is primarily ecological, but it is also economic; it is political, but it is also immigratory; it is material, but it is also social; it impacts the psychologies of those who live with and around it, and it is also impacted by those psychologies; ultimately, it is both produced by and produces the the region. The border then must be conceived dialectically, as a tensioned unity of all the aforementioned contradictions where, as Hegel argued, the dialectical analysis is the “comprehension of the Unity of Opposites, or of the Positive in the negative.”[94] In other words, border walls both are and mean something; that is, they are at once physical structures and psychological edifices. Their physicality is known to those who live amidst and around them and their psychological impact both represents and impacts the societies and states in which they emerge.

As the philosopher Thomas Nail observed, “Every state and state border is criss-crossed and composed of numerous other kinds of border mobilities that cannot be understood by state or political power alone. Critical limology reveals that the state is the product of these more primary process[es] of multiple bordering regimes.”[95] Simply put, the state produces bordering regimes which are themselves historically-contingent, and these regimes similarly produce the state in ways that are formative, corrective, and reproductive. At the heart of such a dialectical motion between produced and producing is the force of motion itself.

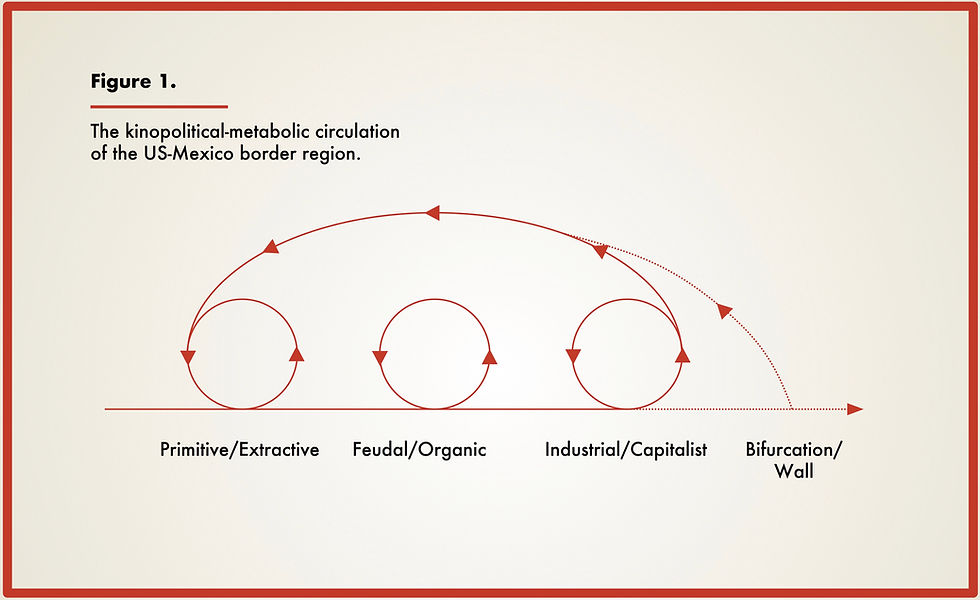

Viewed through a lens of theoretical synthesis, where we begin to incorporate modes of production, metabolism, and kinetics, as in Figure 1 below, we can begin to understand the border as a zone where every circulative junction becomes part of a larger circulation where the forces, modes, and metabolisms of production at once move, collide, and interact with each other. And, along a standard Cartesian coordinate system, where the x-axis represents a forward progression of time, we can begin to understand, firstly, the US-Mexico border region as a zone where primitive production precedes and collides with feudal production, where the expansive and expulsive forces of Spanish conquest violently absorbed and replaced the earlier, indigenous modes; and we can understand, secondly, how the onset of the modern industrial mode, which, as the final junction in a grander historical arc encompassing all three modes—primitive, feudal, and industrial—must still engage in an intercourse with the earlier modes it has both subsumed and replaced. Thirdly, and finally, we can begin to understand that, as is the case with all political and productive hegemonies, other modes in the zone continue to persist and both impact and inform the movement of the zone itself.

In the case of the US-Mexico border region, the final historical moment in this conceptual representation is the point at which militarized wall fortifications begin to emerge; subsuming and drawing from earlier historical border regimes such as the fence, the cell, and the checkpoint. In regard to the present analysis, however, the border wall is an artificial separation and a bifurcation in the metabolism of the region—from a flow of transition, replacement, and movement. The militarized wall also suggests that the kinetic flow of the metabolic movement of capitalism in general can no longer operate in the zone without monumental artifice and divisive edifice; without an increasing militarization to maintain a trajectory which has long outlived its viability. In Figure 1, the US-Mexico border wall thus becomes a regressive and self-destructive device: one which moves retrogressively against even the progression of capitalism itself.

Similarly, in the language of social metabolism and metabolic rift, the wall emerges at the metabolic output site of waste (in the theoretical sense alone), which then catalyzes a back-up of forces thus reinserted back into the circulation of the imperial state’s larger metabolism. In so many words, and unencumbered by the analytical jargon, the border wall stops that which is required for the health of the state—the free flow of people, goods, and resources. In this regard, the border suggests itself as a material signifier of an eventual end—a long, drawn-out end which seems to entail a progressive and total militarization of all geographies claimed by the US; the hard ossification of imperial state boundaries aimed to stop the free flow of people and goods endemic to the region; and the build-up of insuperable kinetic and metabolic pressures.

Thomas Nail observed that, “The wall is the second major border regime of the U.S.-Mexico border. Although the usage of walls as social borders first emerged as the dominant form of bordered motion during the urban revolution of the ancient period, its centrifugal kinetic function persists today.”[96] The wall, according to Nail, acts, contradictorily, as both a force of expansion and expulsion—dominant themes of the border walls of every epoch—and works to push power out from a central point. On this, Nail observed that:

"The wall regime adds to the territorial conjunction of the earth’s flows a central point of political force: the city. [...] Kinetically, the wall regime is defined by two functions: the creation of homogenized parts (blocks) based on a central model, and their ordered stacking around a central point of force or power."[97]

The wall along the southern United States border is emblematic of a bordering regime which not only merges and subsumes prior regimes, but which also represents an historical peculiarity endemic to our time: a new kind of wall—a wall of capitalism. A wall which signifies and represents both a rift and a bifurcation in the imperial social metabolism of the United States; a wall which seems to prefigure the build-ups of pressures responsible for an eventual internal collapse of the imperial state itself; and, maybe most importantly, a wall which acts as a type of negative feedback loop—acting to catalyze the movement of waste, immobility, and ossification back into a failing system which itself becomes increasingly septic, volatile, and deadly. It is the logical conclusion of a long history of racism and imperial violence carried out in the name of colonialism, captialism, and conquest; the result of centuries of incursions, genocide, and expulsions which characterize not only the imperial impetus of Europeans in the Americas more generally, but the very nature of captialism itself to act in ways that are politically, demographically, and ecologically catastrophic.

ENDNOTES

1. Brown 121 2. Martinez, Border People xvii-xviii 3. https://www.ajc.com/news/national/trump-border-wall-speech-read-the-full-transcript/Zm6DfoKTbOb6mOvzxOBLwI/ 4. Angus 183 5. Neuman 15 6. Border Management Modernization 37-38 7. Dunn 170 8. McLinden 1-2 9. Marshall 3 10. Ganster 20 11. Vélez-Ibáñez 20

12. Vélez-Ibáñez 21

13. Ibid. 21 14. Ganster 20-21

15. Cronon 12 16. Galeano 2 17. Wilder et al. 344 18. Ganster 19 19. EPA, Ecological Restoration in the U.S.-Mexico Border Region 11 20. Casey and Watkins 9 21. Ibid. 14 22. The Log of Christopher Columbus’ First Voyage to America the Year 1492, qtd. in Galeano 24 23. Forsythe 297 24. Beaud 15 25. Ibid. 14-15 26. Ganster 21 27. Beaud 15 28. Ibid. 19 29. Haring 7 30. Ganster 23 31. Ibid. 23 32. Ibid. 23 33. Ibid. 23 34. Truett 18-19 35. Ganster 24 36. Ibid. 24 37. Ganster 27 38. Truett 21 39. Ibid. 22 40. Nevins 19 41. Nevins 19 42. Truett 33 43. Truett 34 44. St. John 15 45. Truett 34 46. Ganster 28 47. Nevins 19 48. Martínez 11 49. Martínez 12 50. Nevins 21 51. Nevins 22 52. Ganster 32

53. Nevins 23

54. St. John 2

55. Martin 5

56. St. John 2

57. Nevins 25

58. St. John 2

59. Ibid. 2 60. Martínez 35

61. Martínez 46

62. Ibid. 47 63. St. John 91

64. Ibid. 123

65. Dunn 11

66. Ibid. 11 67. Hernández 5 68. "United States Enacted Border Patrol Program Budget by Fiscal Year" 69. Dunn 81 70. Ibid. 76 71. Trump, emphasis added 72. Dunn 1 73. Brown 145 74. https://www.dhs.gov/news/2018/12/12/walls-work 75. https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/DHS%20BIB%202019.pdf 76. Ibid. 3 77. Ibid. 3, emphasis added 78. Neuman 5 79. Nail 167 80. Byrd viii 81. Herzog 13 82. DHS, “FY 2019 Budget in Brief” 4

83. Dunn 156 84. Hernández 224 85. https://www.vox.com/energy-and-environment/2017/4/10/14471304/trump-border-wall-animals 86. https://news.stanford.edu/2018/07/24/border-wall-threatens-biodiversity/

87. Ehrlich et al., 740

88. Martínez 148 89. Martínez 151-152

90. Truett 184 91. Ganster 1 92. Staudt 10-11 93. Qtd. in Mezzadra and Neilson 16 94. Hegel, “General Concept of Logic” 73

95. Nail 223 96. Nail 183 97. Ibid. 183

WORKS CITED

@realdonaldtrump. “The Wall is the Wall, it has never changed or evolved from the first day I conceived of it. Parts will be, of necessity, see through and it was never intended to be built in areas where there is natural protection such as mountains, wastelands or tough rivers or water.....”Twitter, 18 Jan. 2018, 03:15 a.m.

Angus, Ian. A Redder Shade of Green: Intersections of Science and Socialism. Monthly Review Press, 2017.

———. Facing the Anthropocene: Fossil Capitalism and the Crisis of the Earth System. NYU Press, 2016.

Beaud, Michel. A History of Capitalism: 1500-2000. Monthly Review Press, 2001.

Brown, Wendy. Walled States, Waning Sovereignty. Zone Books, 2010.

Byrd, Bobby, and Susannah Byrd, eds. The Late Great Mexican Border: Reports from a Disappearing Line. Cinco Puntos Press, 1996.

Casey, Edward S., and Mary Watkins. Up Against the Wall: Re-imagining the US-Mexico Border. University of Texas Press, 2014.

Cronon, William. Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists, and the Ecology of New England. Hill and Wang, 2011.

Department of Homeland Security. FY 2019 Budget in Brief. Homeland Security, 2019. Department of Homeland Security. “Walls Work.” DHS.gov, 12 Dec. 2018, accessed 10 Aug. 2019.

Dunn, Timothy J. The Militarization of the U.S.-Mexico Border 1978-1992: Low Intensity Conflict Doctrine Comes Home. CMAS Books, 1996.

Ehrlich, Paul, et al. “Nature Divided, Scientists United: US–Mexico Border Wall Threatens Biodiversity and Binational Conservation.” BioScience. 2018, vol. 68, no. 10, pp. 740-743.

Forsythe, David P. Encyclopedia of Human Rights, Volume 4. Oxford University Press, 2009.

Galeano, Eduardo. Open Veins of Latin America: Five Centuries of the Pillage of a Continent. NYU Press, 1997.

Ganster, Paul. The US-Mexico Border Today: Conflict and Cooperation in Historical Perspective. Rowman and Littlefield, 2016.

Haring, Clarence. The Spanish Empire in America. Oxford University Press, 1947.

Hernández, José Angel. Mexican American Colonization During the Nineteenth Century: A History of the US-Mexico Borderlands. Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Hernández, Kelly Lyttle. Migra! A History of the U.S. Border Patrol. University of California Press, 2010.

Herzog, Lawrence. Where North Meets South: Cities, Space, and Politics on the US-Mexico Border. University of Texas-Austin, 1990.

Marshall, Tim. The Age of Walls. Scribner, 2018.

Martin, Thomas. Greening the Past: Towards a Social Ecological Analysis of History. International Scholars Publications, 1997. ———. "Shapes of Contempt: A Meditation on Anarchism and Boundaries." Social Anarchism 45 (2012): 22.

Martinez, Oscar J. Border People: Life and Society in the US-Mexico Borderlands. University of Arizona Press, Tucson, 1994.

Martínez, Oscar Jáquez. Troublesome Border. University of Arizona Press, 2006.

McLinden, Gerard, et al., eds. Border Management Modernization. The World Bank, 2010.

Mezzadra, Sandro, and Brett Neilson. "Between Inclusion and Exclusion: On the Topology of Global Space and Borders."Theory, Culture & Society 29.4-5 (2012): 58-75.

Nail, Thomas. Theory of the Border. Oxford, 2016.

Neuman, Michael. “Rethinking Borders.” Planning Across Borders in a Climate of Change. Routledge, 2014.

Nevins, Joseph. Operation Gatekeeper and Beyond: The War on Illegals and the Remaking of the US–Mexico Boundary. Routledge, 2010.

Staudt, Kathleen. Free Trade? Informal Economies at the US-Mexico Border. Temple University Press, 1998.

St. John, Rachel. Line in the Sand: A History of the Western U.S.-Mexico Border. Princeton University Press, 2011.

Truett, Samuel. Fugitive Landscapes: The Forgotten History of the US-Mexico Borderlands. Yale, 2006.

Vélez-Ibáñez, Carlos G. Border Visions: Mexican Cultures of the Southwest United States. University of Arizona Press, 1996.

Wilder, Margaret, et al. "Climate change and US-Mexico border communities." Assessment of Climate Change in the Southwest United States. Island, pp. 340-384, 2013.

Comments